🤍 El paradigma del amor: cómo pueden salvarnos las minisemillas

Olvídate del pánico a Trump: así es como pequeñas asambleas alimentadas por el amor podrían derribar el sistema y encender una revolución.

En nuestro debate estratégico mensual Free As A Bird, describí cómo la reelección de Trump no es el final de la revolución. Es una oportunidad para empezar. En la siguiente grabación y transcripción de mi charla, esbozaré cómo este momento podría ser el detonante que necesitamos para construir un nuevo mundo, uno basado en el amor, no en el poder. Cambiando nuestra forma de pensar, organizando asambleas y fomentando una conexión profunda, podemos contrarrestar la desesperación y el fascismo por igual.

Hablo de la necesidad humana fundamental de amor y de cómo transforma la política, basándome en la psicología y en ejemplos prácticos. Desde historias personales hasta planos de asambleas, expongo una hoja de ruta para crear movimientos de masas capaces de lograr un cambio real. Disfrútalo.

También puede escuchar la charla en Soundcloud o dondequiera que consigas mi podcast.

Transcripción

Hola a todos,

Todos estamos pensando en la victoria de Trump en las elecciones estadounidenses. Es fácil, ¿verdad?, entrar en modo pánico. Todo es terrible; todo parece tan desesperanzador.

Lo que quiero sugerir en esta charla es que todo esto está muy lejos de ser cierto. De hecho, que Trump vuelva a ganar las elecciones bien podría ser el detonante para que la gente por fin se ponga las pilas y cree el nuevo mundo que todos queremos.

Por supuesto, no hay garantías de que esté diciendo tonterías. Podría ser terrible y desesperante. Pero lo que quiero decir es que, al mismo tiempo, existe un enorme potencial para hacer lo contrario. Como siempre, depende de nosotros -de nosotros en esta llamada- y especialmente de nuestra voluntad de trabajar juntos en lo que funciona mejor y actuar de acuerdo con el espíritu de ser los humanos que somos.

Entonces, ¿cuál es el plan?

Lo primero que tenemos que mentalizarnos es que toda nuestra forma de ver el mundo tiene que cambiar por sí misma. Aquí no hay atajos. Esto es crucial.

La razón por la que tenemos pánico es porque hemos aprendido a ver el mundo de una manera de suma cero, de una manera política de "nosotros y ellos". Sólo hay poder, y ahora ellos tienen mucho, así que estamos perdidos. Es un sistema de lucha y huida, y sencillamente no es cierto.

La forma en que se nos enseña a pensar en política es en sí misma una ideología insidiosa: que sólo existe el poder: yo contra ti.

Como algunos de ustedes saben, desde hace tiempo vengo señalando que la necesidad humana fundamental es el amor, no el poder. Y cuando digo esto, no me refiero en absoluto a algo sensiblero o sentimental, a un deseo.

Cuando hablo de amor, lo hago en un sentido clásico o bíblico. Es un acto, no un sentimiento: el acto de mejorar el bienestar del otro. Necesitamos dar y recibir amor.

El amor es atención, reconocimiento. Básicamente no se puede sobrevivir psicológicamente sin el otro, sin amor. Necesitamos amor cuando nacemos y estamos indefensos; morimos sin él. Y cuando nos acercamos a la muerte, necesitamos el amor de los demás para que nos cuiden. Durante las décadas intermedias, también lo necesitamos: de la pareja, de los amigos, de los compañeros de trabajo.

¿Entiendes lo que quiero decir? Cuanto más lo piensas, no hay nada idealista en este punto de vista: es bastante obvio. Y como digo, no hay nada sentimental en esto, porque el deseo de dar y recibir amor es en realidad un deseo furioso. Si se nos niega, nos volvemos destructivos, para los demás o para nosotros mismos, y muy a menudo para ambos.

Tenemos que empezar por aquí porque esto nos permite replantear el interés propio. Como dice la frase, el deseo de poder no es la necesidad fundamental, sino simplemente una estrategia para satisfacer nuestra necesidad fundamental: la necesidad de amor.

En otras palabras, el amor es lo primero. La estrategia del poder es una forma deficiente de conseguirlo. No funciona o, como mínimo, es radicalmente subóptima. Digámoslo así.

Y, por supuesto, como cualquier esquema fundacional, esta idea sobre el amor no puede demostrarse de forma concluyente. Tiene un elemento mítico: un sentimiento de lo que somos. Pero, como mínimo, es una visión más atractiva de la humanidad que todo eso del "otro que".

Ahora, mostrarán que hay una gran cantidad de pruebas empíricas de cómo funciona. Puede que algunos de ustedes conozcan algunos de estos ejemplos, así que disculpen si los repito de nuevo, pero creo que llegan al núcleo de cómo construir una estrategia eficaz para hacer frente al fascismo.

Todos sabemos que una crisis climática, en la práctica, en cómo nos va a afectar, lo más probable es que no sea directamente por tormentas o inundaciones. Lo que va a ocurrir -lo que nos va a acabar (matar)- son los efectos secundarios, omnipresentes: es decir, la perturbación política, el colapso social y la toma del poder por defecto por parte de fuerzas fascistas.

Lo que acabamos de ver con Trump, por lo tanto, es sólo un primer recordatorio de cómo esto va a suceder. Pero solo ocurre porque las fuerzas progresistas no se han puesto las pilas, porque no entienden cómo funciona el ser humano y no consiguen organizarse sobre la base de ese conocimiento.

Todos sabemos que no hay nada más importante que esto. El fascismo en el poder: todos sabemos adónde conduce.

Veamos, pues, algunos ejemplos de cómo pueden ocurrir cosas que apoyen el marco del amor en la acción humana.

Empecemos por algo que tiene cierta gracia: ¿por qué los hombres fascistas dejan de serlo?

Sí, lo tienes: cuando consiguen novia. No recuerdo si es la razón principal, pero sin duda lo es. Cuando la gente recibe amor, atención, reconocimiento, dejan de ser fascistas.

De hecho, hay toda una serie de estudios en los que la gente ha entrado conscientemente en espacios de extrema derecha, ha escuchado a personas, se ha hecho amiga de ellas, y luego estas personas muy a menudo vuelven a abandonar ese espacio. ¿Por qué? Porque reciben atención y reconocimiento.

Otra pregunta: ¿cuál fue la principal enseñanza de los recientes disturbios ingleses? Fue cuando una joven musulmana y sus amigas salieron de una mezquita con platos de bocadillos y se los dieron a los airados manifestantes. En cuestión de minutos, ya estaban charlando; admitámoslo, no puedes resistirte a una buena samosa.

Yo mismo utilizo este enfoque una y otra vez. En las 200 y pico charlas públicas que he dado sobre la crisis, aparecen teóricos de la conspiración y gente de derechas que intentan interrumpir mi discurso. Hago un trato con ellos: escucharles a fondo en el debate posterior. Después, los reúno en círculo y me limito a escucharles, a resumir sus preguntas... y luego siguen. Se irán.

Recuerdo que apareció probablemente el conspiranoico más importante del Reino Unido, y tras sentarse con él y sus diez seguidores durante, digamos, 20 minutos, se levantó, me dio la mano y se fue.

Y luego está la historia de que llegué tarde a una boda. Sí, cogí un taxi. El conductor se enteró de que yo era un defensor del clima. Empezó a despotricar sobre los focos de calor y todo eso. Apoyé todo lo que dijo, escuchando todos sus puntos. Y entonces, cuando me bajé al final del trayecto, sacó la cabeza por la ventanilla y me dijo: "Mira, si pudiera permitírmelo, me compraría un coche eléctrico mañana mismo".

Así que esta última historia no es exactamente significativa desde el punto de vista científico: no hice 100 conversaciones de taxi. Pero hay gente que lo ha hecho una y otra vez, y funciona. Y puedes entender por qué funciona si sitúas tu perspectiva dentro del paradigma del amor en lugar del paradigma de la ideología del poder.

La inmensa mayoría de la gente cree cosas no porque sean ciertas en sí mismas, sino porque la creencia es un medio para conseguir lo que realmente quieren, que es atención y reconocimiento, que se les escuche. Quieren amor. Y si alguien o alguna operación llega y lo hace realmente bien, entonces creerán lo que tú crees en su lugar.

Por eso la formación de opinión en las redes sociales es tan superficial. La gente cambia de opinión si se sienta con una persona agradable que le escucha y ve las cosas de otra manera en cuestión de minutos. ¿A quién le importan una mierda las redes sociales? No pueden competir con lo real: una conversación humana.

No estoy siendo ingenuo. Como con cualquier grupo social, hay una curva de ley de potencia. Lo que significa, por ejemplo, que el 80% de los partidarios de Trump cambiarán de opinión si se les escucha con coherencia. Puede que el 19% se resista y necesite un buen puñado de conversaciones para que al menos tenga dudas. Y el 1% son, francamente, psicópatas, y nunca van a cambiar, o casi nunca.

Todos los grupos son así. Piensa en los presos: El 80% de los chicos de esta prisión en la que estoy deberían salir mañana mismo y recibir un apoyo adecuado, una ayuda constante. Pero podría decirse que el 1% no debería salir nunca, porque está muy acabado.

En otras palabras, necesitamos un análisis seccional.

Tenemos que ser sofisticados en lo que decimos. Nada de esto es nuevo. El psicólogo más influyente del siglo XX, Carl Rogers, como quizá sepas, descubrió científicamente en los años 50 que escuchar a las personas y darles una consideración positiva incondicional era la mejor manera de ayudarlas a sanar y crecer.

Fue una revolución en la comprensión de la persona y condujo a un cambio masivo en la forma de ver el sufrimiento psicológico y la necesidad de asesoramiento.

Así pues, necesitamos una revolución similar en lo que llamamos política. Hay que apartarla del paradigma económico que la ha dominado durante cientos de años -todo eso del interés propio- y entregarla a la psicología. La política como rama de la psicología, no de la economía. La política es la necesidad de atención en el contexto de las decisiones sociales. Eso es todo lo que es.

Entonces, ¿cuál es el equivalente de la revolución contable para hacer frente a la angustia social y política? Esta es la parte emocionante: es la revolución de la asamblea. Es decir, escuchar, pero a escala social.

Sacaré la cabeza aquí y diré que estamos seguros en un 80% de poder crear un movimiento de masas diez veces mayor que la Rebelión de la Extinción utilizando este método. Organizaciones que puedan competir con el fascismo, no con el poder, sino disolviendo ese poder a través de los mismos mecanismos que Rogers descubrió: a través de la escucha.

En este momento, estoy trabajando con el equipo de Assemble en el Reino Unido, y hemos ideado microdiseños y procesos que, cuando se repitan, deberían permitir que las asambleas crezcan exponencialmente, para crear campañas críticas que puedan tomar el control de ayuntamientos y gobiernos. Es así de grande.

No voy a entrar en todos esos detalles en esta charla, obviamente, pero estoy escribiendo un libro sobre ello, como es el caso.

Dicho esto, permíteme ser lo más claro posible: no debes centrarte en las grandes cosas del final, sino en el aquí y ahora. Tú, escuchándome ahora. El momento más importante, con diferencia, en la creación de un movimiento social -y ya lo he hecho varias veces, así que sé de lo que hablo- es la primera reunión.

Recuerda, XR empezó con 15 personas en una habitación. La Última Generación en Alemania empezó con cinco jóvenes miserables en una llamada de Zoom; lo recuerdo bien. Acabo de leer hoy que Podemos, el partido de izquierdas más popular de Europa, empezó con una reunión de 28 personas.

¿Y cuántas personas están en esta llamada? Mira a tu alrededor-exactamente. Así que todo estará bien.

Así que, de nuevo, ¿cuál es el plan? El plan es empezar. Un primer paso. Así de sencillo.

Robin va a esbozar la creación de grupos regionales Rev21 en todo el mundo a partir de los pocos miles de personas que tenemos en nuestra lista de correo. Tanto si son muchas personas como si no, se basarán en una región o incluso en una ciudad. Cuando sólo haya unas pocas personas, el grupo podría abarcar un país entero.

Acordaréis reuniros cuatro veces y, durante ese tiempo, cada persona se comprometerá a organizar por sí misma una miniasamblea con otros activistas, amigos, familiares, conocidos, en línea o fuera de línea, lo que mejor funcione.

Pero, en realidad, basta con unas pocas personas: entre cinco y diez. El desarrollo de la miniasamblea es muy sencillo, pero es fundamental que te ciñas al formato.

Se empieza dando vueltas y cada persona escucha a los demás. Cuentan cuál es su historia, cómo ha sido su vida hasta llegar aquí y cómo han llegado al encuentro.

El segundo paso de la miniasamblea consiste en volver a dar la vuelta y que cada persona comparta lo que cree que no va bien en su ciudad, en su país o incluso en el mundo. Una vez más, todos hablan y todos son escuchados. Después, se debate un poco sobre lo que la gente tiene en común.

Por último, en la última ronda, cada persona propone tres o cuatro cosas que quiere que cambien. Puede tratarse de políticas concretas, formas de organización o grandes temas que les preocupan. Juntos, el grupo se pone de acuerdo sobre cuatro o cinco cuestiones o reivindicaciones clave que comparten.

Luego viene la parte crítica: se invita a todos los miembros del grupo a organizar ellos mismos una miniasamblea. Por ejemplo, alguien podría organizar una en Perth. A su vez, se anima a esos participantes a hacer lo mismo. Y así sucesivamente.

Un mini-montaje sólo lleva entre una hora y una hora y media. No es gran cosa. Quizá quieras empezar o terminar con algo de comida para que sea agradable y social. Pero a lo largo de varias iteraciones, si de cada miniasamblea inicial surgen otras cinco, podríamos implicar a decenas de miles de personas en sólo dos o tres meses. Haz cuentas.

Esto crea el impulso necesario para una serie de asambleas fuera de línea en las zonas locales. Estas asambleas pueden formar consejos alternativos para hacer demandas locales, o incluso presentar candidatos comunitarios a las elecciones. Es una vía clara de la acción colectiva al poder, lo que la hace creíble.

Y junto a esto, hay concentraciones, marchas, sentadas, resistencia fiscal y, por supuesto, mi favorito personal: el banquete.

Hay unas 50 páginas de detalles al respecto, que aún se están puliendo, pero Rev21 es un lugar excelente para ponerlo en marcha. Y no es algo que vayamos a hacer de forma aislada, sino en conexión con proyectos existentes en distintos países.

Si todo esto le parece un poco exagerado, permítame recordarle la historia reciente. En muchos países occidentales, las campañas han pasado de cero a convertirse en grandes protagonistas en cuestión de meses.

Por ejemplo, el partido griego Syriza pasó del 4% al 40% durante la crisis de la deuda en tan solo un año. Podemos en España pasó de la nada al 20% en las elecciones más o menos en el mismo tiempo. Macron en Francia construyó un movimiento en seis meses haciendo que sus partidarios escucharan a 50.000 personas sobre los cambios que querían. Jeremy Corbyn pasó de ser un don nadie político a liderar el Partido Laborista en meses. ¿Y Bernie Sanders? Empezó con un 2% de reconocimiento de su nombre y construyó un movimiento de medio millón de voluntarios para competir por la nominación demócrata.

La lección es clara: cuando no hay una auténtica opción de izquierdas, la gente vota a los fascistas. Ha ocurrido una y otra vez en la historia.

Ahora bien, todas esas campañas que he mencionado tenían importantes problemas culturales y de diseño. Y eso es una buena noticia. ¿Por qué? Porque podemos aprender de sus éxitos a medias para crear algo que realmente cambie el mundo, para crear una nueva civilización. No porque seamos arrogantes o arrogantes, sino porque a menos que lo hagamos, a menos que cambiemos todo el sistema, nada cambiará. Y lo inimaginable quedará encerrado.

Así que, ¡qué momento para estar vivo, amigos!

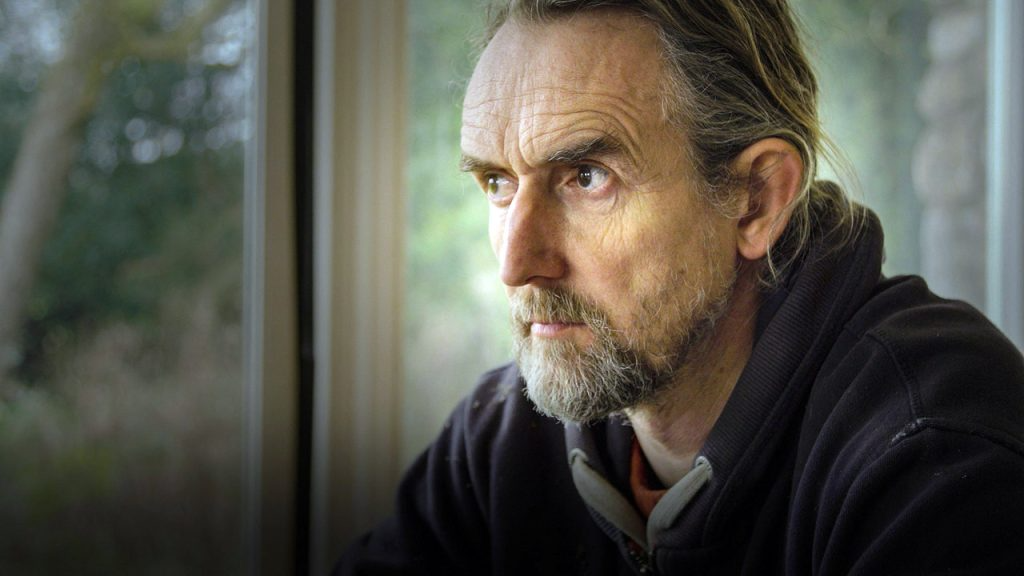

Una última cosa: estoy bastante alegre con las perspectivas, y lo digo desde una celda de la cárcel. Así que no tienes excusa para no animarte y ponerte manos a la obra.

Esto llevará unos meses -muy posiblemente unos años-, pero no podemos fingir que no tenemos una estrategia que podría funcionar. Así que tenemos que hacerlo.

Bien, muchas gracias a todos. Gracias por todo vuestro increíble trabajo. Os envío todo mi amor. Adios.

¿Quieres participar en el proyecto Mini-Assembly? ¡Inscríbete!